HATS OFF TO THOSE WHO KEPT ON WEARING HATS

BARE HEADED—-THE BRAVE NEW ERA

Hats were more than fashionable they were required

When ever you see a photo of a crowd from around the turn of the last century, up until the 1960’s, it seemed that practically every man and most women were wearing a hat regardless of their economic status or profession. When did the wearing of hats become unpopular? After about 1964, nowadays, if you walk down Flinder Street, travel by Bus or Train or attend race meetings you will see very few people wearing a wide brimmed hat. They have became so rare you might have thought that the hat itself was the cause of diseases – like skin cancers. The reason we wore hats, like other clothing items, was to protect our skin. In addition, less exposure to the sun delayed the development

of cataracts (reason for wide brim hats). Our ancestors had developed the habit of wearing hats, not necessarily because of fashion or religion.

Up until the 1960’s, most men would have no more left the house without a hat than they would without trousers. Bankers and stockbrokers made the commute into the city wearing bowler hats, gentlemen took to the streets in straw boaters and manual workers passed through the factory gates wearing cloth caps.

The crowd shots of sporting events like the FA Cup in the 30’s and 40’s showed a sea of brims, peaks and ribbons. The type of hat men wore then may have been dependent upon their station, but regardless of class men did not venture out in public without a hat upon their head. Maybe it was the clever 1960’s style of advertising campaigns as well as Hollywood stars that brought on the craze for sun glasses with the useless baseball cap, that contributed to the demise of proper hats even though Ophthalmologists recommended that sun glasses be worn with a wide brimmed hat when exposed to long periods of sunlight.

Skin cancer in Australia

Table 1 shows the latest national incidence count of melanoma, as provided by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW), and the number of paid Medicare services for non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC: basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma) based on Medicare records. The latest mortality statistics for melanoma and NMSC are provided as reported by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) for 2015.

According to the latest ABS data, of the Australians living with cancer in 2011-12, nearly one in three (32.6%) had skin cancer, making this the most common type of cancer.[1] Medicare records show there are over 950,000 paid Medicare services for non melanoma skin cancers each year[2] – more than 2,500 treatments each day.

At least 2 in 3 Australians will be diagnosed with skin cancer before the age of 70.[3] The risk is higher in men than in women (70% vs. 58% cumulative risk of NMSC before age 70[3]; 60 vs. 39 age-standardised incidence rate of melanoma.[2]) The risk of mortality is also higher for men – 67% of Australians who die from skin cancer are men.[4]

Skin cancer causes more deaths than transport accidents every year in Australia.[4]

Table 1 Australian incidence and mortality for non-melanoma skin cancer (NMSC) and melanoma

| Men | Women | Total | |

| Incidence[2] | |||

| NMSC (number of paid Medicare services, not people*) 2014 | 600,482 | 358,761 | 959,243 |

| Melanoma 2012 | 7,060 | 4,976 | 12,036 |

| Total | n/a | n/a | n/a |

| Mortality 2015[4] | |||

| NMSC | 453 | 189 | 642 |

| Melanoma | 1,004 | 516 | 1,520 |

| Total | 1,457 | 705 | 2,162 |

* Medicare data for numbers of services for NMSC in 2014 are available,[2] otherwise latest incidence data for NMSC is from 2002.[5]

NMSC mortality includes deaths from the common skin cancers (SCC & BCC) and deaths from the rarer variants like Merkel cell tumours, dermatofibroma protuberans, and others.

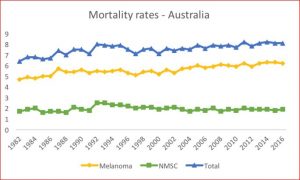

Although ABS data show that skin cancer mortality rates have increased since 2000 (Figure 2.1), recent trends in Australia suggest stablisation or slight decline among those under the age of 45 years in melanoma[6] and non-melanoma skin cancer incidence rates.[7] This is consistent with earlier observations of stable incidence trends among young people in Australia, who are likely to have reduced their UV radiation exposure as a consequence of long-running public education campaigns to improve sun protection. A similar pattern has been observed for several other high-risk countries including New Zealand, North America, Israel and Norway.[6] These recent changes illustrate the importance of decreased UV exposure in childhood as a key contributor in lowering skin cancer risk later in life.[6]

Figure 1 Mortality rates in Australia 1982 to 2016.[2]

Back to top

Melanoma incidence and mortality

Melanoma of the skin is the third most commonly diagnosed cancer in males (after prostate and bowel cancer) and females (after breast and bowel cancer) In Australia.[8] In 2016, an estimated 13,280 new cases of melanoma will be diagnosed in Australia, and 1,770 people will die.[2]

Table 2 Australian incidence and mortality of melanoma

| Men | Women | Total | |

| Incidence 2012[2] | |||

| Count | 7,060 | 4,976 | 12,036 |

| Age-standardised rate | 59.9 | 39.2 | 48.7 |

| Mortality 2015[4] | |||

| Count | 1,004 | 516 | 1,520 |

| Age-standardised rate | 7.9 | 3.5 | 5.5 |

In Australia, the age-standardised incidence rate for melanoma increased by 181% between 1982 and 2016, from 27 cases per 100,000 to an estimated 49 cases per 100,000.[2] However, how much of this increase is due to a real increase in the underlying disease, and how much is due to improved detection methods, is unknown. The incidence of melanoma of the skin rose at around 5.0% per year during the 1980s, moderating to 2.8% per year after that up until 2010.[9] It is predicted that the initial rapid increase is partly attributable to individual behaviour and the use of solariums, resulting in increased exposure to solar ultraviolet radiation.[10][11] The moderated trend after the 1980s is consistent with increased awareness of skin cancer and improved sun protective behaviours as a result of extensive skin cancer prevention programs dating back to the 1980s.[2]

Gender

Australian women have a 1 in 24 chance of being diagnosed with melanoma before the age of 85, whereas men have a 1 in 14 risk of being diagnosed with melanoma before the age of 85, based on 2011 AIHW figures.[8]

The age-standardised incidence rate of melanoma increased from 1982 to 2016, with this increase more marked for men than women (a 214% vs. 150% increase). There were an estimated 60 cases per 100,000 males and 39 cases per 100,000 women in 2016.[2]

It is expected that melanoma in men will continue to increase to about 74 cases diagnosed per 100,000 men in 2020, equating to approximately 10,780 cases per annum.[12] Among women it is expected that melanoma will continue to increase slowly to about 45 new cases diagnosed per 100,000 women in 2020, equating to approximately 6,790 cases per annum. The largest increase in rates of both genders is expected to occur at the age of 65 and above.[12] It should be noted that these projections have been extrapolated from 1982-2007 incidence trends and do not take into account the future impact of skin cancer prevention campaigns, or the impact of reduced solarium use.

Gender differences are also observable in relation to mortality. Overall, Australians have a 1 in 129 chance of dying from melanoma by age 85 – men have a 1 in 84 chance and women a 1 in 240 chance.[8]

Death rates for melanoma among men increased from 6.4 deaths per 100,000 in 1982 to an estimated 9.4 deaths per 100,000 in 2016; however, most of this increase occurred before 2005, and rates have remained fairly stable over the past decade.[2] In women there was a negligible change from 3.2 deaths per 100,000 in 1982 to an estimated 3.6 deaths per 100,000 in 2016.[2]

Age

There is an observable age gradient for melanoma incidence according to AIHW data:

- 2% of people diagnosed with melanoma are aged under 40 years;

- 2% are aged 40-49;

- 4% are aged 50-59;

- 4% are aged 60-69;

- 4% are aged 70-79; and

- 3% are aged 80 or older.[2]

The mean age for melanoma diagnosis is 63 years among men and 60 years among women.[8]

While only a small proportion of total melanoma cases are diagnosed in people under 35 years of age, Australian adolescents have by far the highest incidence of malignant melanoma in the world (one-third of cancers in females, one-quarter in males), compared with adolescents in other countries.[13] Furthermore, melanoma is the most common cancer diagnosed in Australians aged 15-29 years, and accounts for more than one-quarter of all cancers in this age group.[14]However, research in Queensland suggests a decline in the incidence of thin invasive melanoma since the mid- to late 1990s among young people who have been exposed to Queensland’s primary prevention and early detection programs since birth.[15]

Location

Australia’s high incidence of skin cancer is attributable to a combination of its predominantly fair-skinned population and high levels of ambient UV radiation due to proximity to the equator.[16][17][18]

According to 2012 IARC and WHO data, New Zealand has a slightly higher age-standardised incidence rate than Australia (35.8 vs. 34.9 per 100, 000 people), and mortality rate (4.7 vs. 4.0 per 100, 000).[19] Melanoma incidence rates in Australia and New Zealand are more than two to three times higher than those in Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. Although mortality rates are quite low, they are still more than two times higher in Australia and New Zealand than in Canada, the United States, and the United Kingdom.[19]

However, there is promising data that suggests a recent stabilisation or slight decline in melanoma incidence rates in Australia over the last 10 years.[6]

Within Australia, people in Queensland face the highest risk of developing melanoma, followed by Western Australia, New South Wales, Tasmania, Australian Capital Territory, Victoria, South Australia, and Northern Territory.[2]

Melanoma incidence rates in regional and remote areas are higher than in major cities.[2] Particularly high mortality rates were observed for those who lived in inner or outer regional areas.[2]

Socio-economic status

In Australia, there is no clear association of melanoma with socioeconomic status.[2] The mortality rate is highest in the second and third lowest socioeconomic groups, and lowest in the highest socioeconomic group.[2]

Indigenous status

In 2005–2009, data from New South Wales, Queensland, Western Australia and the Northern Territory shows that the incidence of melanoma was 9.3 cases per 100,000 among Indigenous Australians, compared with 33 cases per 100,000 among non-Indigenous Australians.[2] Mortality rates were also lower for Indigenous Australians (2.3 deaths per 100,000) compared with non-Indigenous Australians (6.4 deaths per 100,000).[2]

Non-melanoma incidence and mortality

Although skin cancer accounts for 81% of all new cases of cancer diagnosed in Australia each year, it is often reported that breast cancer is the most common cancer in women and prostate cancer is the most common in men. That’s because most Australian cancer registries don’t routinely collect data for these more common forms of skin cancer – only the most serious, melanoma.[20] Non-melanoma skin cancers (NMSC) are often self-detected and are usually removed in doctors’ surgeries, sometimes without histological confirmation due to destructive treatment techniques, or treatment with topical creams[3] where tumour sites are only excised in post-treatment testing.

As the latest incidence data is estimated from self-reported, histologically confirmed (81.5%) and unconfirmed, NMSC treated in 2002,[3][5] Medicare service numbers are provided as a proxy measure below.

Table 3: Australian incidence and mortality of Non-Melanoma Skin Cancers

| Men | Women | Total | ||

| Incidence | 2014[2] (number of paid Medicare services, not people*) | 600,482 | 358,761 | 959,243 |

| Incidence per 100,000 | 2002[3] (estimated from survey) | 1,531 | 1,036 | 1,271 |

| Mortality | 2013[21] | 416 | 176 | 592 |

* Medicare data for numbers of services for NMSC in 2014 are available,[2] otherwise latest incidence data for NMSC is from 2002.[5]

NMSC mortality includes deaths from the common skin cancers (SCC & BCC) and deaths from the rarer NMSCs like Merkel cell tumours, dermatofibroma protuberans etc.

Non-melanocytic skin cancer accounted for 959,243 paid Medicare services in 2014 as evaluated from data on NMSC excisions, curettage, laser, or liquid nitrogen cryotherapy treatments.

Findings from the annual BEACH surveys of general practice conducted from 2006 to 2016 showed that skin cancer predominated as the cancer most often managed (by way of medications, clinical and procedural treatments, ordering of pathology or imaging tests) in GP-patient encounters, and was consistently among the top ten conditions managed by GPs.[22]

Despite the high incidence rate of non-melanoma skin cancer, the age-standardised mortality rates are relatively low at 2.8 deaths per 100,000 population for males and 1.1 deaths per 100,000 for females.[2]

Economic impact

According to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, skin cancer cost the health system over $400 million in 2008-9 ($367.37m non-melanoma and $49.5m melanoma) – the highest cost to the system of all cancers.[23][24]

In 2010 it was calculated that the total cost of NMSC (diagnosis, treatment and pathology) was $511.0 million.[25] In 2015 NMSC treatment was estimated to increase to $703 million.[25]

Survival

In Australia, relative survival after diagnosis of melanoma of the skin is very high when compared with other types of cancer.[2] In 2007-2011, individuals with melanoma of the skin had a 90% chance of surviving for at least five years compared with the general population.[2] Increases in melanoma survival were seen between 1980s and 1990s, 5-year survival increased from 86% in the period 1982-1987 to 91% in 1994-1999, however since the 2000s melanoma survival has stabilised. [26]

In the period 2007-2011[2]:

- Five-year relative survival was greater for women compared with men (94% cf. 88%).

- Survival was high for all age groups, gradually declining with age (95% 5-year survival for those below 40 years as compared with 80% for those aged 80 years and over).

- Although survival was high overall it varied considerably by tumour thickness. Five-year survival was almost 100% for small tumours (1mm or less), but only 54% for large tumours thicker than 4mm.

- No significant differences in survival by remoteness or by socioeconomic status were observed.

Australian survival rates from melanoma are generally higher than in other countries due to the high proportion of thin lesions, according to the Cancer Epidemiology Centre at Cancer Council Victoria. Survival rates are higher in countries where there is greater melanoma awareness due to earlier detection.[27]

As it is not mandatory to report non-melanoma skin cancers—more common, but far less deadly than melanoma—to cancer registries, incidence and prevalence statistics are not routinely available.[28] ?As a consequence, there is no corresponding five-year survival data for non-melanoma skin cancer.

5 Comments

Hats off to someone was a gesture of praise/appreciation seldom used today.

A hit song titled “Hats off to Larry”, was written and sung by Del Shannon in 1961, shortly before men suddenly stopped wearing hats.

My daughter found this little ditty on the internet

Chorus

Like when you say,

Hats off, to sunny Saturdays,

Hats off, to choc’late anything,

Hats off, to friends loyal and true.

And that’s why we’re takin’ our hats’ off to you.

Before it became easy to buy a car people spent a lot more time outside. Wearing a hat was practical because it helped keep you dry and protected you from the sun. Even if you took a bus, you’d have to wait for it outside, and if there was no bus, train or tram, you were walking. Another point not mentioned, besides owning a car, was the rise of suburbia. The car meant people could live outside Melbourne which was all the go in the sixties, unlike today, people wanted to leave the hustle and bustle of the city behind. Along with a home, a lawn, and a couple of kids, came a more relaxed lifestyle, and the formality of hats fell by the wayside. In fact, all formality fell by the wayside including the wearing of suits which seemed also to diminish during this period.

One of the reasons people stopped wearing Hats was because they did not like their hair being messed up. It might not have mattered so much if they could have left their them on at the office or going out to dinner, but that would not be unacceptable today.

The slip on a shirt, slop on sun screen and slap on a hat campaign has been a success but we need to tighten the law regarding Solariums. They are supposed to be illegal in Australia, but the purchase and use of UV tanning beds for private use at home is allowed. As a result many are still operating privately and/or are selling their units on the black market to backyard operators who have no shortage of customers. Its seems there are still people who are prepared to risk getting skin cancer for the sake of an all year tan and scum bags to exploit them.

I paid a penalty for believing a base ball cap would protect me because, now, at age 60 years, every six months, I am getting chunks of flesh cut out of my neck and ears butfortunately they are not the melanoma variety. Throw away these stupid caps and get yourself a proper hat that will protect you!